While working on a personal project, RainbowRedux, I’ve discovered the content is authored in some interesting ways. Today I’m going to talk about large distances, floating point numbers and the errors they can cause. I’ll show how I’m trying to reduce these distances and make the geometry more manageable.

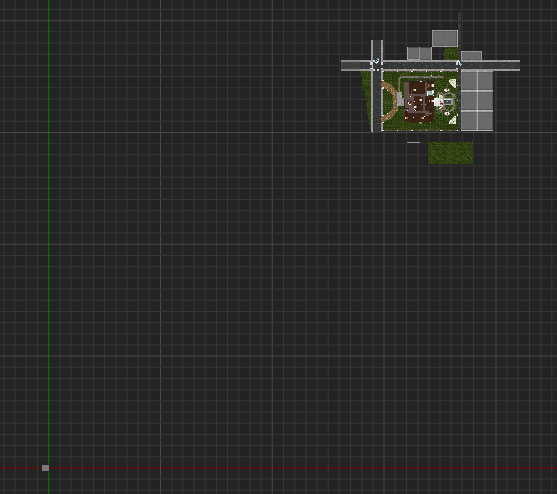

In this image you can see that the level geometry is stored in the top right, approximately 50,000 units away from the origin (roughly ([30 000],[30 000],[30 000])). In the bottom left you can see there is some geometry at the origin. This is all the dynamic objects like breakable glass, usable doors and so on. I haven’t been able to find a reason for this. I suspect it’s just how some of their authoring tools were configured.

This is another top down view. Watch as I rotate a room. As it rotates you can see that the pivot point is the origin. Imagine the room is on a large invisible boom arm. All rooms and static objects are stored like this in the level.

There are 2 problems here. First, having the pivot point of the geometry at the origin and having the geometry so far away limits flexibility to manipulate that geometry. As you can see even a simple rotation doesn’t act as you’d expect. It also affects the calculated bounding box which means the engine will assume the geometry is much larger than it actually is.

The second problem comes down to potential for floating point precision errors. It’s not drastic yet, but the further you move away from the origin, the more imprecise floating point math becomes. This becomes more apparent as more operations are performed on large numbers. As objects rotate, scale, translate, and get manipulated during gameplay this can manifest in strange ways.

Floating Point Precision

Floating point numbers are not stored precisely on computers. Floating Point Demystified does a great job of explaining the maths, the workings and the implications. Demystifying Floating Point Precision is a shorter article which is less comprehensive in it’s explanation but gets to some practical implications quicker.

The relevant practical implications are basically:

- There are varying levels of precision

- Currently game engines primarily use single precision floating point numbers for performance and compatibility reasons

- Single precision floating point numbers can only reliably provide about 6-7 significant digits of precision.

- That means you can store really accurate numbers close to zero, however the larger the number the less accurately it can be represented.

Assuming a scale of 1 unit = 1cm, that means on a given axis when 30,000 units or more away we can assume we’ll get around 1mm of precision in the worst case which isn’t too bad. However that is only if no operations are performed. Once objects are that far out, start moving, get manipulated each frame, get scaled, rotated and translated, that precision error compounds leading to a much greater chance for incorrect calculations.

Exactly the level of scale you can expect to achieve and when you will expect to see problems will vary engine to engine. Since the imprecision compounds it can be difficult to say when you will experience problems. It will depend on the number and order of transformation operations before the final game state is calculated and rendered.

In an extreme case during development of Rising Storm, one level started exhibiting really strange aiming behaviour. You couldn’t adjust aim by just a pixel or 2, instead it would jump 5-10 pixels at a time. After a fair bit of investigation we discovered the level was actually around 300,000 units away from the origin. This is an extreme example where it was very noticeable, however even with lesser magnitudes errors can appear in strange ways such as seams in geometry and subtle collision errors which may manifest as frustrating errors like inaccurate or missed collision when players are engaged in a fight.

For UE4 the most precise information I found is that physics is limited in levels to 500,000 units. There are a few comments around that it has been increased now, although there are no hard recommendations on maximum size. In general it’s good practice to work as close to the origin as possible.

How to solve this?

For the purposes of this example, I’m just going to ignore the dynamic objects at the origin, and focus only on the static objects that are far away.

Step 1. For each object an Axis Aligned Bounding Box is calculated.

Step 2. Calculate the centre of the bounding box. This becomes the offset for the object.

Step 3. Subtract the object offset from each vertex.

This places the object so it’s centered at the origin. In the image above you can see the cardinal axis lines (red and green) that are shown at the origin in the UE4 editor, and you can see the vehicle rotating about it’s own center.

Step 4. Move the object by the object offset.

This places the object back in its original position, however if we were to rotate the object it rotates in place rather than moving as if on a boom arm.

Step 5. Combine the AABBs for all objects to calculate a world AABB. This makes it easy to identify the global offset of the level

Step 6. Move each object back by the global offset

This keeps the relative position of all the objects, but centers the level around the origin. In this picture you can see the level is intersected by the cardinal axis lines.

Results

By shifting the origin of the level the potential for floating point imprecision is reduced. This also allows the geometry and objects to be manipulated at runtime more easily as they will exhibit more expected behaviour when being transformed.

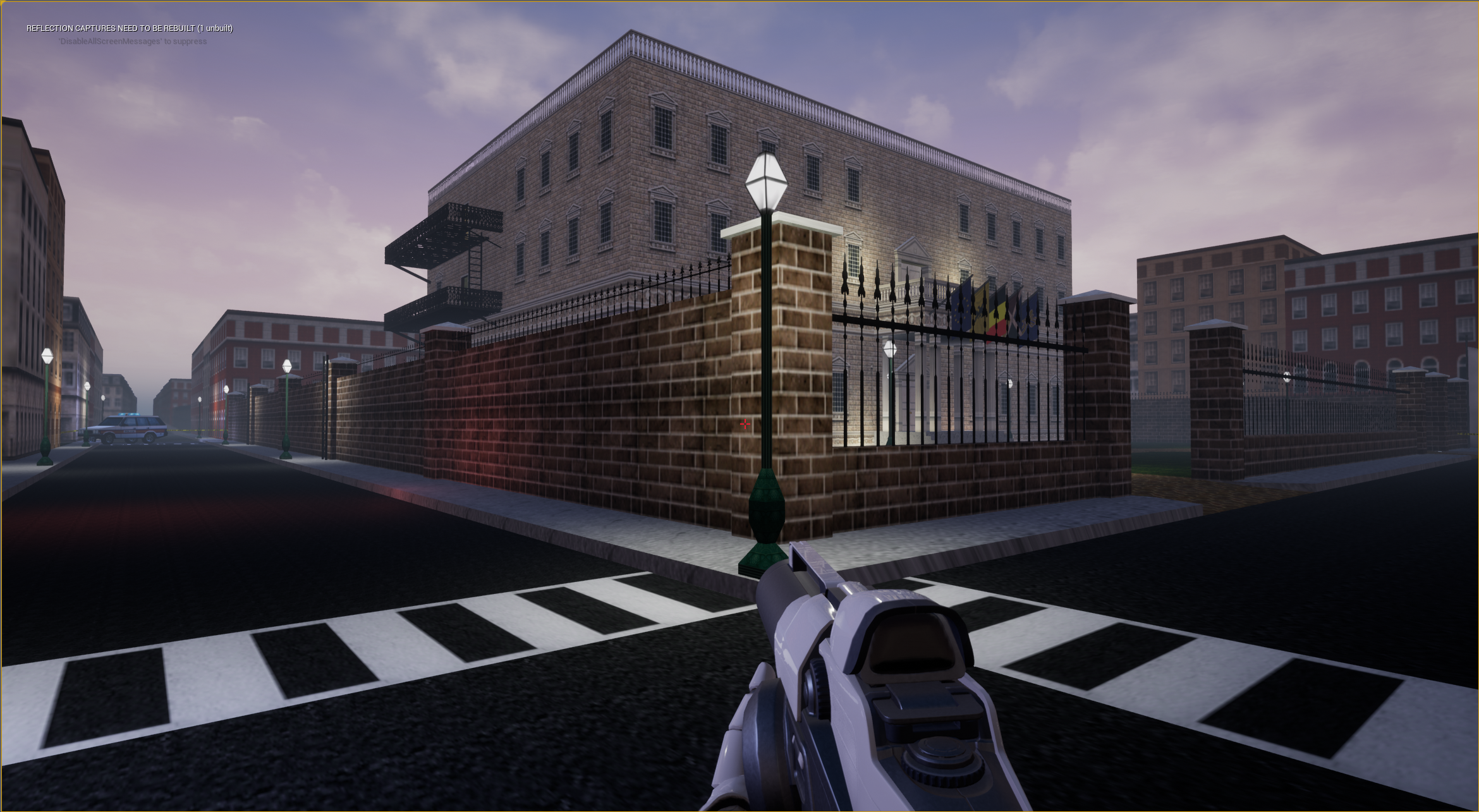

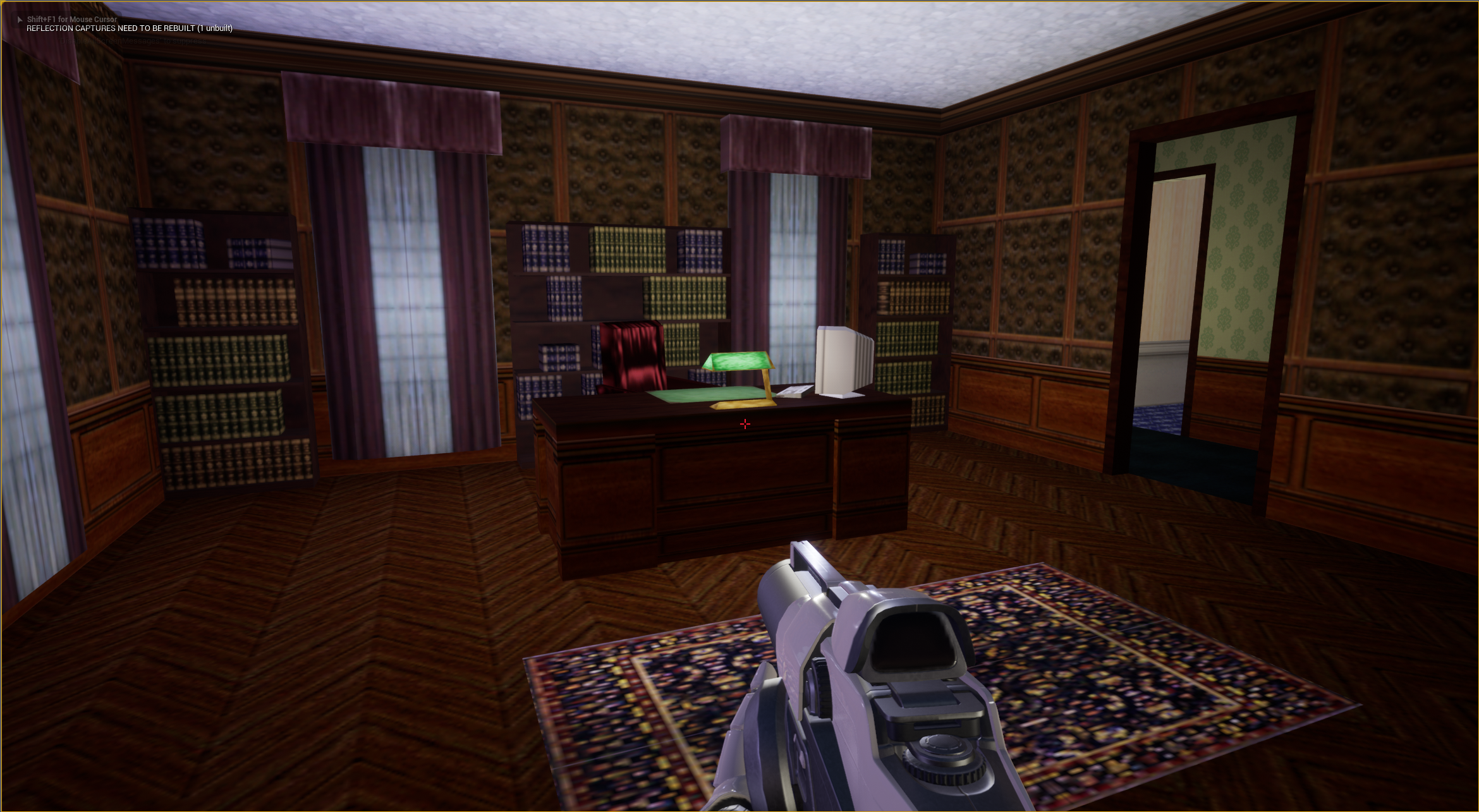

Here are a few screenshots from the project showing some progress.

Share